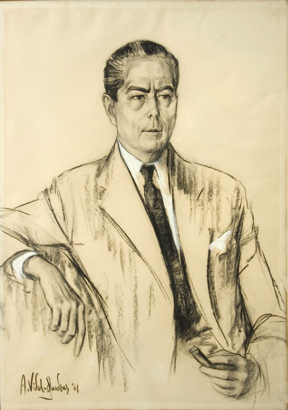

J. M. William Turner

Londres, Inglaterra, 1775 - Chelsea, Inglaterra, 1851

Turner was born in London, England, on April 23, 1775. He was the son of a barber and wigmaker, and his genius made itself manifest early: his first signed drawings, copies of prints, date from 1787. His early art studies were with draughtsman Thomas Malton (1748-1804). On December 11, 1789 he was admitted into the Royal Academy in London. That same year he began producing his albums with views of London and landscapes from surrounding areas. In 1793 he obtained the Greater Silver Ballet, a prize given by England's Society of Arts. Fishermen at Sea (1796, Tate Gallery, London), his first oil painting, was shown at the Royal Academy in 1796. In 1799, at just 24 years of age, he was elected an associate member of the Royal Academy and three years later he was made an effective member. From that moment on, his public recognition would only increase, as did the number of commissions he received. In 1803 he inaugurated a gallery at his own home in London on Harley Street, in order to exhibit his works. In 1807 he published the first volume of his Liber Studiorum, a manual illustrated with his prints on landscape painting. That same year, on November 12, he was named professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy, where he gave classes uninterruptedly until 1828, although he maintained the post officially until 1837. In 1822, Turner presented seventeen watercolors at a show organized by William Bernard Cooke in Soho Square, in London. He participated in this show with watercolors again in the years that followed. In 1823, King George IV commissioned him with a large painting on the battle of Trafalgar for the St. James palace in London. The canvas was excessively criticized and the artist was accused of having committed many errors. In 1836 his annual envoy to the Royal Academy was also criticized, since, according to his accusers, he had moved away from a faithful representation of nature. Writer John Ruskin (1819-1900), who would later become his friend and a great collector of his work, came to his defense. In the first volume of his book Modern Painters, published in 1843, he asserted the superiority of modern landscape artists-Turner among them-compared to their predecessors. In 1839, the artist exhibited 40 watercolors in the Music Hall at Leeds. In 1843 he studied Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Theory of Colors in an English translation, and applied it in his paintings. In 1845, due to the president of the Royal Academy's being ill, he held the position during almost a year. The last of his travels correspond to this era. Throughout his lifetime, Turner traveled with great frequency, finding motifs for his works on his trips. As early as 1791 he toured various locations in England to make drawings of the landscape. He visited Bath and Bristol, among other places. He traveled abroad for the first time in 1802 and visited Switzerland and France, where he remained in Paris for one season. In 1816 he went to Yorkshire and Lancashire, in England, and the following year he traveled to Amsterdam, in Holland, and the Rhine region. One year later he traveled to Edinburgh to illustrate Provincial Antiquities of Scotland, a book by Walter Scott (1771-1832). Between 1819 and 1820 he made his first trip to Italy and visited the cities of Milan, Venice, Florence, Rome, Naples, Sorrento and Paestum. The fascination he felt for what he encountered there is reflected in his work and in the fact that he returned to this country time and again, in 1828, 1833, 1840 and 1843. The illustrations that he made for Italy, published in 1830 by English poet Samuel Roger (1763-1855), are also a demonstration of this. In 1825 he traveled to Holland, the Rhineland and Belgium, and the following year, to Brittany and the valleys of Meuse, Moselle and Loire in France. We also owe his Picturesque Views of England and of Wales to his trips to Great Britain, a book with illustrations based on his watercolors, the first part of which was published in 1827. Two years later he traveled to France again; he stopped in Paris and visited Normandy and Brittany. Turner toured continental Europe intensively during the 1830s and until 1845. Afflicted with health problems and able to paint only with difficulty, he spent the last years of his life in the residence he acquired in 1846 at 6 Davis Place on Cremorne New Road, in Chelsea, a suburb of London. He exhibited for the last time at the Royal Academy in 1850, after having participated in their annual show every year since 1796. He died in London one year later, on December 19th. His remains were buried on the 30th of that month in the crypt of St. Paul's cathedral in the same city.

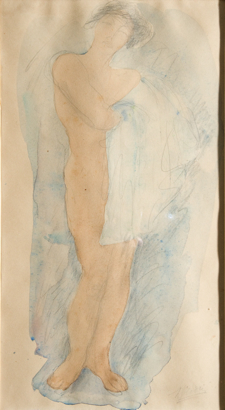

Juliet and her Nurse, 1836

Oil on canvas, 88 x 121cm

In Juliet and her Nurse, Joseph Mallord William Turner presents a view of the main Piazza and the eastern parts of Venice from high above the western end of the Procuratie Nuove, close to the rooftops of the Hotel Europa in which he stayed. At the centre is the Campanile and Basilica of San Marco, the red bricks of the tower emphasizing the unnaturally whitened, almost ghostly domes. To its right is the distinctive upper level of the Doge's Palace, which appears somewhat compressed in Turner's rendering of it. The building with the attenuated cupola to the right is the Zecca, or Mint. Just above this, two vertical strokes of Turner's brush indicate the famous columns of the Lion of San Marco and San Theodore, standing in the Piazzetta. From there the paved Riva degli Schiavoni stretches into the distance, fringed by countless boats. Off to the right, fireworks explode above the larger vessels moored in the harbour alongside Palladio's church of San Giorgio Maggiore. In the square, a mass of revellers are dressed for carnival, their attention divided between musicians, puppet shows and the burst of fireworks alongside Florian's café.

This work is a nocturnal scene where fire erupts into the darkness, captivating the onlookers. Some scholars have speculated that Turner exploited these effects to play on the wellestablished comparison between the formerly great Venice, then subject to Austrian law, and contemporary London.

The title of the picture, however, invoked Shakespeare's play Romeo and Juliet, the festive Piazza presumably standing in for the Capulet's ball. The young John Ruskin (1819-1900), later an influential writer on art and society, was among those who have taken up the challenge of defending Turner's iconography and his alleged topographical infelicities in the depiction of Venice. But, ultimately, the picture needs no apologist, for it is one of the most appealingly atmospheric canvases of the second half of Turner's career: its powerful combination of dynamic perspective and punctuating bursts of light is readily apparent.